| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jcgo.org |

Review

Volume 3, Number 3, September 2014, pages 81-84

Vaginal Lactobacillosis

Gary Ventolinia, b, Caroline Schradera, Evelyn Mitchella

aTexas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 800 W. 4th Street, Odessa, TX 79763, USA

bCorresponding Author: Gary Ventolini, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 800 W. 4th Street, Odessa, TX 79763, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication June 10, 2014

Short title: Vaginal Lactobacillosis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo278e

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Vaginal Lactobacillosis (VL)

- Etiology

- Associated Conditions

- Prevalence

- Clinical Diagnosis

- Laboratory Diagnosis

- Differential Diagnosis

- Therapy

- References

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Lactobacilli are the most abundant bacteria found in normal vaginal flora. Vaginal lactobacillosis (VL) is manifested as a very annoying, profuse white vaginal discharge, with the sensation of incessantly having wet the underwear. It is characterized by the presence of abundant and extremely longer than normal lactobacilli in vaginal wet mount preparations. The etiology is unknown and the prevalence is approximately 15%. Lactobacillosis should be differentiated from candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis and cytolytic vaginosis. The most effective treatment of VL is oral amoxicillin-clavulanate, using doxycycline as an alternative.

Keywords: Vaginal; Lactobacilli; Bacteria

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Lactobacilli are the most abundant bacteria found in normal vaginal flora. The lactobacilli most frequently found in women are L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners and L. jensenii. These bacteria are responsible for maintaining a healthy balanced vaginal environment and inhibiting pathogenic bacterial growth. They exert their inhibition by several mechanisms, including competing for binding receptors on vaginal epithelial cells thus hindering pathologic microorganisms from adhering. Lactobacilli also exert their inhibition by producing bacteriocins, hydrogen peroxide, and lactic acid that function as antibacterials. Lactic acid inhibits the growth of bacterial vaginosis species and N. gonorrhea. Additionally a recently identified bacteriocin, lactocin 160, targets the cytoplasmic membrane of Gardnerella vaginalis [1]. Hydrogen peroxide suppresses the growth of Gram-negative and Gram-positive facultative and obligate anerobes [2], including such organisms as E. coli, Gardnerella vaginalis and Mobilincus species and could also protect against human immunodeficiency virus infection [3].

| Vaginal Lactobacillosis (VL) | ▴Top |

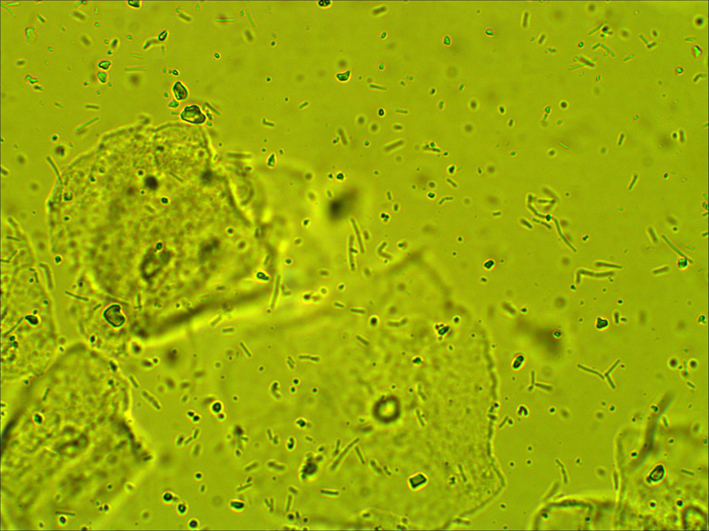

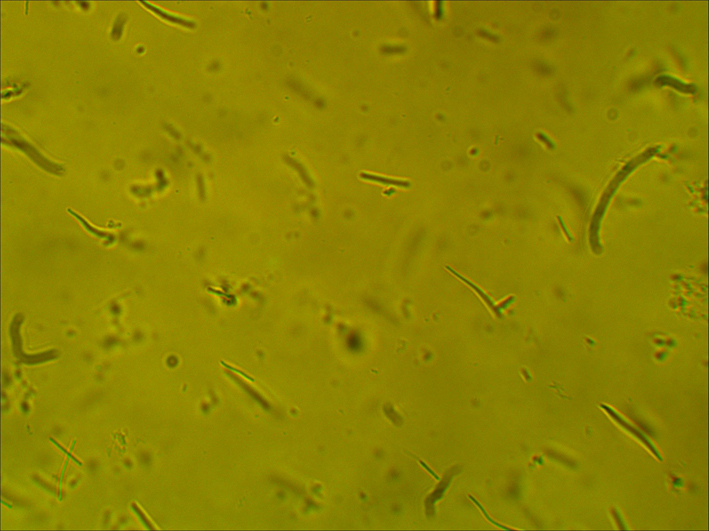

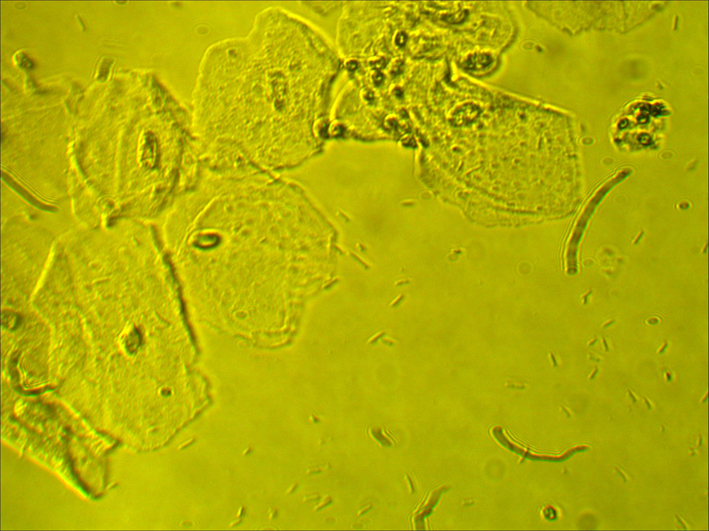

VL is a condition characterized by the presence of extremely long lactobacilli in vaginal wet mount preparations. In asymptomatic women vaginal lactobacilli usually measure between 5 and 15 µm in length, as seen in Figure 1. Patients with VL have abundant, long, segmented lactobacilli chains (also known as leptothrix), ranging between 40 and 75 µm in length [4, 5] as seen in Figure 2. A normal wet mount preparation is illustrated in Figure 3 as a comparison.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Abundant and extremely longer than normal lactobacilli in vaginal wet mount preparation (× 400). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Abundant, long, segmented lactobacilli chains (also known as leptothrix), ranging between 40 and 75 µm in length (× 600). |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Normal wet mount preparation (× 400). |

| Etiology | ▴Top |

The cause of VL is mysterious and several authors like Kaufman and Faro have stated that since the organism behaves commensally, lacking evidence to the contrary, it may safely be ignored [6]. Ferris et al have postulated that increased availability of OTC anti-fungals misused by self-diagnosed fungal infections may be contributing to the transformation of normal lactobacilli [7].

| Associated Conditions | ▴Top |

It is interesting to note that Ricci et al postulated the hypothesis that lactobacillosis causes an increased production of lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide. This may contribute to the damage of epithelial cells, nerve endings, and receptors therefore serving as a risk factor for the development of vulvodynia [8].

Another thought-provoking correlation was found by Korenek et al between diabetes mellitus and lactobacillosis. They suggested that patients with diabetes mellitus could be more prone to developing lactobacillosis since lactobacilli are more abundant in women with high serum glucose levels [2].

| Prevalence | ▴Top |

The prevalence of VL according to Feo et al is around 15% in patients who complain about abundant vaginal discharge [9].

| Clinical Diagnosis | ▴Top |

Clinically VL is manifested by profuse although variable white vaginal discharge, at times vulvar itching, a burning feeling in the vaginal introitus that follows urination, and the sensation of incessantly having wet the underwear. The constant cleaning of the perineal area is very annoying to these patients.

Generally no vaginal odor is evident. According to Horowitz et al, the symptoms occur regularly, are most apparent in the progestinic phase of the menstrual cycle and more manifested before menses [5].

There are usually no other clinical associated findings in the vulva, vagina, or cervix of symptomatic patients with VL. Also their vaginal acidity is within normal limits.

| Laboratory Diagnosis | ▴Top |

At fresh wet mount microscopy using physiologic saline solution without additive coloring or fixation, VL usually presents as more than 50 lactobacilli present per field at a high power magnification (× 400). The average length of the lactobacillus according to Horowitz et al was 60 µm in the studied patients with lactobacillosis and 10 µm in their comparison group [4].

| Differential Diagnosis | ▴Top |

There are over 10 million office visits per year for vaginal complaints in the USA. Several vaginal conditions may have clinical presentations that are similar to VL; therefore, a precise diagnosis is crucial to attain a targeted therapy [3].

In the differential diagnosis of lactobacillosis it is imperative to include candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis and cytolytic vaginosis. These four conditions are easily distinguished by clinical examination accompanied by vaginal pH measurement and wet mount microscopy.

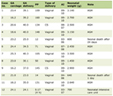

Cytolytic vaginosis usually exhibits a low pH (3.5 - 4.5) and at wet mount microscopy numerous intermediate epithelial cells, lactobacilli, and cytoplasmic debris (plain/stripped nuclei from cytolyzed epithelial cells) could be present. Additionally, a Pap smear is diagnostic for cytolytic vaginitis. Candidiasis typically presents with a normal pH (< 4.5) and at potassium hydroxide preparation buddying fungi, hyphae, and/or pseudo hyphae are present. A summary is shown in Table 1 [10, 11].

Click to view | Table 1. Differential Diagnostic Criteria for Candidiasis, Bacterial Vaginosis, Lactobacillosis and Cytolytic Vaginosis |

Lactobacillosis and candidiasis are frequently confused. The vaginal fourchette might be sensitive at speculum insertion and bimanual examination [12]. Consequently patients with the above conditions might have a history of unsuccessful treatment with diverse anti-fungal medications [12].

| Therapy | ▴Top |

The most effective described treatment of VL is 500 mg of amoxicillin-clavulanate to be given orally every 8 h for 7 days. Horowitz et al reported that 86.3% of his patients became asymptomatic after the above treatment. For patients that were penicillin allergic he reported prescribing 100 mg of doxycycline every 12 h for 10 days. The patients remained clinically and laboratory asymptomatic at their 18 months follow-up visit [5]. Cepicky et al published in 2003 a series of patients with lactobacillosis treated with vaginal nifuratel. The authors observed 22.2% relapses after 1 month [13].

| References | ▴Top |

- Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, Girerd PH, Jefferson KK, Buck GA. A new era of the vaginal microbiome: advances using next-generation sequencing. Chem Biodivers. 2012;9(5):965-976.

doi pubmed - Korenek P, Britt R, Hawkins C. Differentiation of the vaginoses-bacterial vaginosis, lactobacillosis, and cytolytic vaginosis. Internet J Advanc Nurs Pract. 2003;6(1).

- Suresh A, Rajesh A, Bhat RM, Rai Y. Cytolytic vaginosis: A review. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2009;30(1):48-50.

doi pubmed - Bibbo M, Harris MJ. Leptothrix. Acta Cytol. 1972;16(1):2-4.

pubmed - Horowitz BJ, Mardh PA, Nagy E, Rank EL. Vaginal lactobacillosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(3):857-861.

doi - Kaufman RH, Faro S. Benign Diseases of the Vulva and Vagina. 4th ed. St. Louis (MO): Mosby; 1994:353-380.

- Ferris DG, Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD, Soper D, Pavletic A, Litaker MS. Over-the-counter antifungal drug misuse associated with patient-diagnosed vulvovaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(3):419-425.

doi - Ricci P, Troncoso JL. Lactobacillosis and chronic vulvar pain: looking for high risk factors as precursors in women who develop vulvodynia. J Minimal Invas Gynecol. 2013;20(6).

doi - Feo LG, Dellette BR. Leptotrichia (Leptothrix) vaginalis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1952;64(2):382-386.

pubmed - Demirezen S. Cytolytic vaginosis: examination of 2947 vaginal smears. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2003;11(1):23-24.

pubmed - Wathne B, Holst E, Hovelius B, Mardh PA. Vaginal discharge—comparison of clinical, laboratory and microbiological findings. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994;73(10):802-808.

doi pubmed - Hills RL. Cytolytic vaginosis and lactobacillosis. Consider these conditions with all vaginosis symptoms. Adv Nurse Pract. 2007;15(2):45-48.

pubmed - Cepicky P, Malina J, Kuzelova M. [Treatment of aerobic vaginitis and clinically uncertain causes of vulvovaginal discomfort]. Ceska Gynekol. 2003;68(6):439-442.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.