| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.jcgo.org |

Original Article

Volume 11, Number 4, December 2022, pages 101-107

How the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed a New Mother’s Sense of Loneliness, and Who Was Key to Helping Them Through It

Ai Miyoshia, Yutaka Uedaa, e, Asami Yagia, Toshihiro Kimuraa, Eiji Kobayashia, Kosuke Hiramatsua, Satoshi Nakagawaa, Takahiro Tabuchib, Yoshihiko Hosokawac, Sumiyo Okawab, d, Tadashi Kimuraa

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan

bCancer Control Center, Osaka International Cancer Institute, Osaka, Japan

cDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tsukuba, Ibaragi, Japan

dInstitute for Global Health Policy Research, Bureau of International Health Cooperation, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

eCorresponding Author: Yutaka Ueda, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka 567-0871, Japan

Manuscript submitted October 13, 2022, accepted December 8, 2022, published online December 30, 2022

Short title: Mother’s Loneliness in COVID-19 Pandemic

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo824

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: We report here on new mothers’ changing sense of loneliness before and after the first year of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and assess what and who they felt were important to them for reducing their loneliness.

Methods: We conducted an online survey of mothers. The questionnaire had sections regarding the home childcare environment, her anxiety and sense of loneliness levels, and whether or not she could consult with.

Results: It revealed that 58.6% of mothers had felt lonely more often than they had before COVID-19 pandemic and that 45.0% had felt lonely within recent 30 days. Mothers who were not working, or who could not get anyone’s help for the first month after childbirth, or who had anxiety about child-rearing or their economic situation, or whose family was unable to respond to her feelings or support her, or who did not have anyone to consult with, or who did not have sufficient opportunities to consult with her friends and neighbors, or who could not consult with, or had refrained from consulting with, pediatric clinic, felt loneliness more often. Mothers who could not consult with their husband, mother, father, brothers, and sisters, mother-in-law, neighborhood friends, or business colleagues felt loneliness more.

Conclusions: A new mother’s perception that her needs were not being met, or whether she could consult with her neighborhood friends or work colleagues as well as her husband, parents, and/or mother-in-law, was associated with more loneliness. Stronger involvement of family and friend in her child-rearing should be promoted.

Keywords: COVID-19; Childbirth; Perinatal care; Loneliness; Social isolation; Key person

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic began in Japan in early February 2020. The pandemic has been relentless, with horrendous impacts on almost all aspects of our lives, forcing Japan to declare a state of public health emergency, which began a period of great social isolation. Most people stayed home, refraining from going out if not necessary, resulting in extreme reductions of in-person socializing with friends and out-of-household family. Working practices also changed dramatically. Working at home was recommended and became common. If women went to work, they maintained social distancing, wore masks, and kept quiet during breaks.

Over the last few years in Japan, there had already been a serious social problem - a steadily growing feeling of isolation among mothers raising young children. Mothers with a strong sense of loneliness are known to be more likely to be depressed and to have decreased self-esteem and poor health, which consequently leads to the poor health of their children, and the possible child abuse [1]. Loneliness is also shown to be influenced by both personal and social factors. Personal factors include introverted personalities or low self-esteem. Our self-conception is considered to be largely based on our relationships with other people [2].

According to a recent study in Germany, obstetric patients’ concerns regarding severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the accompanying pandemic were demonstrated to have increased during the course of the pandemic correlating positively with stress and depression. Of note is the increase in active coping over time and the overall good mother-child-bonding. Maternal self-efficacy was affected in part by the restrictions of the pandemic [3].

In Japan, due to modern lifestyle changes, a small-nuclear family without nearby relatives is becoming the predominant family structure. Dual-earning parents have also been increasing. Official statistics in Japan have shown that one-third of our families now have this kind of small-nuclear structure and that roughly 7% of family units with small children are fatherless [4]. Under this new family culture, the childcare environment has inevitably changed, and it would be often tough for mothers to raise her children. We have theorized that as families become more isolated, the environment surrounding the child-rearing mother has provided reduced support for her from her neighbors and family within her community [5].

So, even before the COVID pandemic, the modern working environment in Japan was thought to be working against mothers who had young children, but the pandemic seems to have severely worsened this problem. The questions we hoped to answer with our survey study are, you can use: Is it true that the pandemic made child-rearing conditions worse? Is it true that connections between families were so sparser during the pandemic; that it was harder to gather childcare information? Is it true that the burden of working under pandemic conditions made balancing work with family more difficult for child-rearing mothers? Throughout the pandemic, for the new-child-rearing mother, the roles of her neighbor and family connections and her working environment have become clearer.

We herein report on the changes in, and causes of, the mother’s sense of loneliness before and after the first year of the COVID pandemic. We have assessed what and who were the most important for preventing the child-rearing mother from feeling lonely.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This was a cross-sectional study that used a subset of the data collected by a larger nationally-representative survey, which we have called the Japanese COVID-19-and-Society Internet Survey (JACSIS). JACSIS was comprised of two surveys, for two target populations: 1) pregnant and post-delivery women; and 2) the partners of pregnant or post-delivery women. The study samples for each survey were retrieved from the pooled panels of an internet research agency (Rakuten Insight, which had approximately 2.2 million panelists in 2019) [6]. Survey participants provided the agency with their web-based informed consent before they responded to the online questionnaire, and they were allowed to stop participation in the survey at any point.

We retrieved survey data from post-delivery women having an infant 1 - 25 months of age at the time of the survey was taken. From July 28 to August 31 of 2021, we collected data on 6,256 female respondents, with valid survey answers from 5,689. The survey had several sections. The first section was consisting of questions regarding the mother’s background (her age, education, employment status, area of residence, her number of children, and whether she lived with her partner). Another section involved the status of her childcare (whether she raised her newborn baby at home or her parent’s place, whether, at 1month postpartum, there was anyone else helping her with her childcare, and whether there were any opportunities to consult with her friends and neighbors regarding raising her children). The other dealt with whether there was a family member who could help her when she had problems, whether her family members could respond appropriately to her feelings, whether there was anyone whom she could consult when she had trouble, and if so, whom she would consult with.

The survey explored the mother’s feelings of anxiety about COVID-19, child-rearing, and economic matters. Of key importance to our investigation was the mother’s sense of personal loneliness, whether she feel loneliness more often during the initial year of the pandemic than during the year before it started, whether she had felt lonely within the last 30 days, whether she had consulted with her pediatric clinic or she had refrained from consulting with it due to the pandemic, and whether she had refrained from routine baby screenings due to the pandemic.

Ethics approval

The Research Ethics Committee of the Osaka International Cancer Institute reviewed and approved the survey study protocol (approved on June 19, 2020; approval no. 20084). The Act on the Protection of Personal Information in Japan was followed by the Internet survey agency.

Statistics

MedCalc was used to calculate differences between groups using the logistic regression test for categorical variables. The level of statistical significance was set at P = 0.05.

| Results | ▴Top |

Characteristics of the internet survey responders

The relevant characteristics of the responding mothers are shown in Table 1.

Click to view | Table 1. Characteristics of the Responders |

Changes in mother’s sense of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

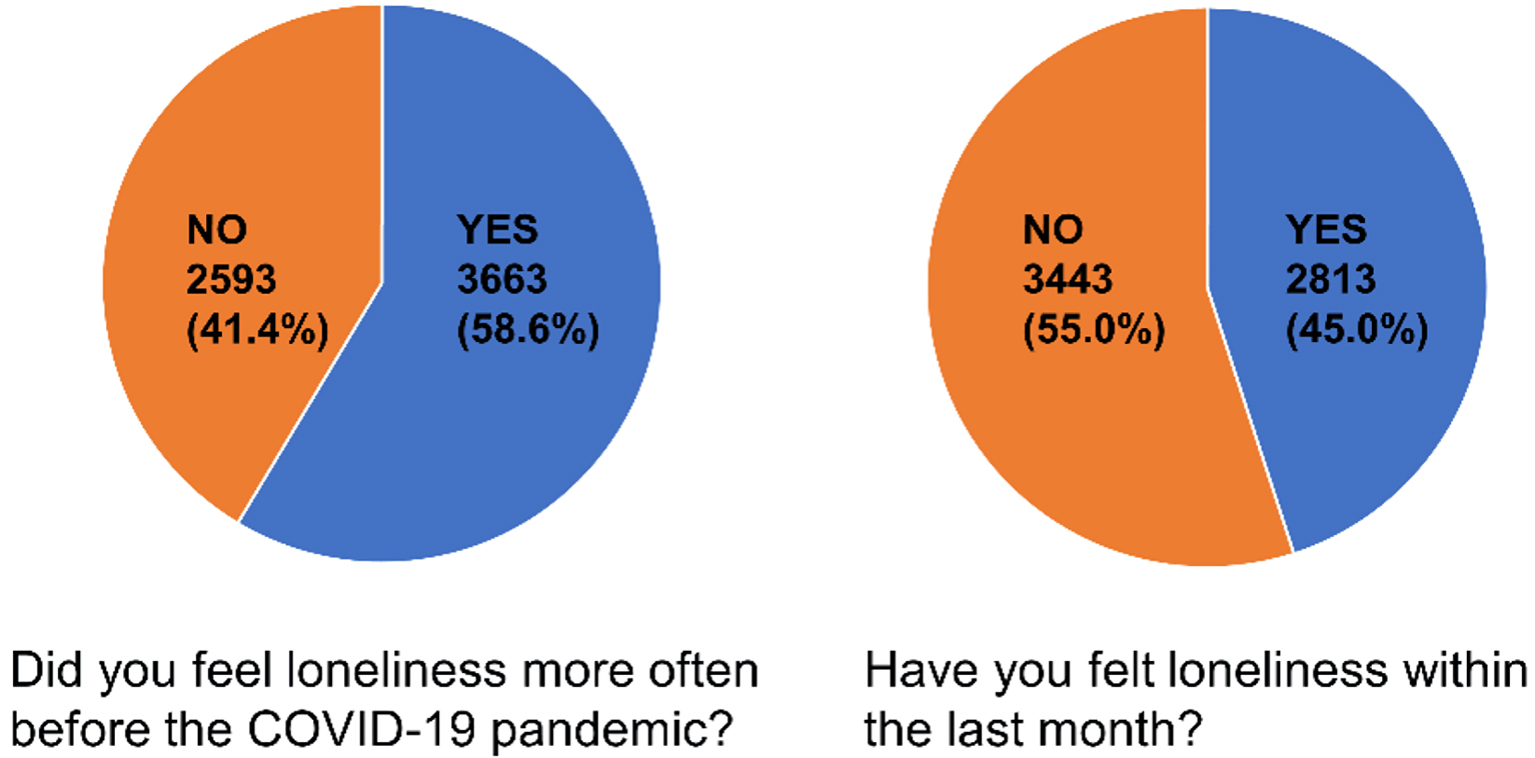

The percentage of surveyed mothers that felt lonely more often during the pandemic than before the pandemic (January 2020) was 58.6%. The reciprocal 41.4% of respondents did not feel differently before or after the onset of the pandemic (Fig. 1). At the time they took the survey (August 2021), only 45.0% had felt lonely within the past 30 days, and 55.0% had not. The percentage of mothers feeling lonely was thus decreasing over time.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Changes in mother’s sense of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study showed that 58.6% of the mothers surveyed felt lonely more often during the pandemic than before the pandemic (before January 2020); 41.4% did not. 45.0% of respondents had felt lonely within the past 30 days; 55.0% had not. The percentage of mothers who felt lonely has recently decreased. COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019. |

Factors influencing the mother’s loneliness

Multivariate analysis, looking for any correlations between the adverse factors faced by the mother and the mother’s sense of loneliness, revealed that she was most likely to be working at the time of the survey (P = 0.0282, odds ratio (OR): 0.8791, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.76 - 0.99), and she could not get anyone’s help during the first month after childbirth (P = 0.0068, OR: 1.2239, 95% CI: 1.06 - 1.42); she had anxieties concerning her child-rearing abilities (P < 0.0001, OR: 2.2570, 95% CI: 2.00 - 2.55), her economic status (P < 0.0001, OR: 1.5437, 95% CI: 1.37 - 1.74), her family’s ability and willingness to respond to her feelings (P < 0.0001, OR: 0.4910, 95% CI: 0.40 - 0.60), her family’s support when she had trouble (P = 0.0133, OR: 0.4910, 95% CI: 0.40 - 0.60), and that there was nobody whom she could consult with when she had problems (P = 0.0024, OR: 2.6611, 95% CI: 1.42 - 5.00). She also worried that there were not enough opportunities to consult with her friends and neighbors about raising her children (P < 0.0001, OR: 2.2334, 95% CI: 1.98 - 2.52). Finally, she was concerned that she could not consult with her pediatric clinic, or she had refrained from doing so due to the pandemic (P < 0.0001, OR: 1.2725, 95% CI: 1.15 - 1.41). These factors all contributed to the new mother’s sense of loneliness.

What was not statistically associated with the mother’s sense of loneliness was the mother’s age, whether her baby was her first-born, whether she gave the baby-rearing duties to her parents, whether she lived with her partner, whether she had anxiety about COVID-19, and whether or not she had refrained from any baby health screening due to the pandemic.

Mothers who felt the most lonely were those who were not working, or who could not get help during the month after childbearing, or who had anxiety about her child-rearing or her economic situation, or whose family she felt could not respond to her feelings, or whose family could not support her when she had trouble, or who did not have anyone whom she felt she could consult when she had problems, or who did not have opportunities to consult with her friends and neighbors about raising her child/children, and who could not consult, or had refrained from consulting, her pediatric clinic due to the pandemic (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Factors Influencing the Mother’s Loneliness |

Types of advisers who influenced the mother’s loneliness

We conducted a multivariate analysis for correlations between the types of advisers whom the mother could have potentially consulted with when she had problems and the mother’s overall sense of loneliness. This analysis revealed that a perceived lack of advice, in descending order of importance, from her husband (P < 0.0001, OR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.56 - 0.81), mother (P < 0.0001, OR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.62 - 0.84), father (P = 0.0001, OR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.70 - 0.88), siblings (P = 0.0076, OR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.76 - 0.96), mother-in-law (P = 0.018, OR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.70 - 0.97), neighborhood friends (P < 0.0001, OR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.60 - 0.76), and work colleagues (P < 0.0001, OR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.60 - 0.80) were significantly associated with the mother’s sense of loneliness. Being able to get advice from her in-laws (other than her mother-in-law) or other distant relatives was not associated with her loneliness, nor was access to advice from her distant friends or school alumni (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 3. Advisers Influencing the Mother’s Loneliness |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, symptoms of depression have been noted worldwide among pregnant and young-child-rearing women [7. 8]. For example, the prevalence of pandemic-related depression in such women was 39.2% in Qatar [9], 56.3% in Turkey [10], 32.7% in Iran [11], 58% in Spain [12], 37-40.7% in Canada [13, 14], and 29.6-33.7% in China [15, 16]. With regards to the levels of depression measured before and during the pandemic, it was reported that an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Survey (EPDS) score greater than 13 was self-reported in 15% of these mothers before the pandemic and 40.7% during the pandemic [14]. Likewise, a moderate to high State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) score of greater than 40 were reported in 29% of these women before the pandemic; this increased dramatically, to 72%, during the pandemic [14].

In addition to loneliness, pregnant women assessed after the onset of COVID-19 also had significantly increased rates of depression symptoms (29.6% vs. 26.0%) compared to pregnant women evaluated before the declaration. Additionally, the prevalence of depressive symptoms increased in parallel with the number of newly confirmed COVID cases, suspected infections, and deaths [15, 16]. It is clear that the pandemic has been one of the biggest factors affecting new mothers’ and pregnant women’s mental health in the past 8 years. In a study from Canada, a higher proportion of mothers had clinically significant depression (35.2%) and anxiety symptoms (31.4%) during the pandemic than at any previous data collection time point (3, 5, and 8-year time-points before the pandemic). The means of scores for depression and anxiety at the time-point within the pandemic were significantly higher than at time points 3, 5, and 8 years prior to the pandemic (8.3 and 11.9, verses 5.1 and 9.5, 5.4 and 9.5, and 5.8 and 10.3, respectively) [17].

These results from Canada were similar to what our investigations found in Japan. Fifty-eight point six percent of the Japanese new mothers surveyed, they felt lonely more often during the pandemic than before it. However, 19 months have now passed while under the pandemic’s constrained social conditions. We have found that the percentage of mothers (in our most recent August 2021 survey) who had felt lonely within 30 days before taking the survey was lower than for mothers surveyed in November 2020, who had felt lonelier during the first year of the pandemic than before the pandemic started (i.e., before January 2020) (Fig. 1).

Going back to January of 2019, one full year before the pandemic began, we were already investigating Japanese mothers’ sense of loneliness as part of another study. We note that the wording of the questionnaire we used in our 2019 study was somewhat different from this current study, but we were still able to glean information useful for this current study.

At the time of our 2019 survey, 56.5% of mothers having an infant 4 - 12 months of age had recently felt loneliness. Twenty-two months later, in November of 2020, as the pandemic had raged on for 9 months and isolation protocols were at their strictest, 61.8% of the respondents reported feeling loneliness (Miyoshi, et al, submitted). By August of 2021, after we extracted similar data regarding women having an infant 4 - 12 months of age, we found that the mother’s sense of loneliness had decreased significantly during the intervening year, from 61.8% to 45.9%.

We can assume that there are numerous individual reasons for the small improvements in a new mother’s feelings of loneliness from Nov 2020 to August 2021. During that period, COVID case-fatality rates were rapidly declining because of vaccines and medical countermeasures being deployed. The new mothers might have been becoming more at ease with the pandemic environment with time and becoming more comfortable with the scope of their semi-limited communication possibilities. The local government might also have been effectively using loneliness countermeasures by recognizing the mental health problems among pregnant women.

These are all reasonable suppositions, but they prodded us to take an additional deep-dive into the root causes of the new mother’s sense of loneliness. Our newest study has surprisingly revealed that anxiety surrounding getting COVID-19 was not significantly associated with the mother’s feelings of loneliness. On the contrary, the mother’s anxiety about her child-rearing capabilities and her economic situation strongly influenced her sense of loneliness (Table 2). Another finding was that, if she felt that “Her family could not respond to her feelings” or that “Her family could not support her when she had trouble”, the mere thought that her demands were not being adequately met seemed to be associated with her loneliness, regardless of whether the situations were real or not.

“She gave up rearing her newborn baby to her parents” was not associated with her loneliness, whereas perceiving that “She could not get anyone’s help during the first month after childbearing” was associated. Whether or not “She had refrained from participating in routine baby health screening due to the pandemic” was not associated with her loneliness; however, whether “She could not consult with, or had refrained from consulting with, her pediatric clinic due to the pandemic” was associated with her loneliness.

We presumed that these associations with loneliness might be triggered by psychological isolation. In our previous study, it was revealed that feelings of stress and a perceived lack of information about childcare were both associated with a new mother’s sense of loneliness (Miyoshi, et al, submitted). The results of this current investigation are very compatible with those. In our new investigation, the mother’s perception that her demands for support and advice were not being met was associated with loneliness. This perception of unfulfilled demands is very similar to a feeling of stress. Results suggested that working outside of the home and/or consulting with her friends in her neighborhood or her colleagues at work might help alleviate the mother’s feeling of stress and make up for the lack of information she would normally receive from close family members.

The mothers who did not have anyone whom she felt she could easily consult with when she had trouble, or who did not have frequent opportunities to consult with her friends and neighbors about raising her child/children, felt lonely more often. Presumable reasons that the mother was feeling more isolated from society than usual during the pandemic might be that, under the declared state of emergency, she had to refrain from going out unless necessary, and when she did go out, she had to keep her social distance from others. In the pre-pandemic past, the new mother could daily consult with her friends and neighbors about child-rearing while she exchanged her older children from kindergarten or as she shopped. These interactions became much more difficult during the pandemic.

When the new mother skipped her routine pediatric clinic visits, that loss of interaction increased her sense of social isolation. This suggests that, professionally, we should find more ways to support new mothers emotionally and try not to increase their sense of social isolation. Perhaps a system of visiting pediatric nurses or specialists would improve this problem.

It is easy to imagine that a Japanese mother would lend a great deal of importance to consulting with her husband, parents, and mother-in-law as advisors during her post-delivery period. We found that whether or not she could consult with her neighborhood friends or her work colleagues was associated with her loneliness. These social contacts played an important role in her life to prevent loneliness, but, due to pandemic-caused social isolation, she spent less time with her neighborhood friends. Particularly important were those interactions with other mothers with similar-aged children and circumstances. Because during the pandemic working at home was highly recommended, new mothers were less likely to travel to work, and even if she did go to work, she needed to keep her social distance and not speak openly to others while having lunch. Thus, new mothers had fewer chances to consult socially and freely with their colleagues about their childrearing issues during the pandemic. We assume that these situations made the mother feel lonelier. It was previously reported that it was important for the mental health of new mothers to be living in trusting neighborhoods, and to have strong supportive social networks, as they were far less likely to cause infant physical abuse (OR 0.25 and 0.59, respectively) [18].

Depending on how you look at it, individuals whom the mother felt were somewhat trustworthy, other than her partner or immediate family, could find additional ways to be helpful towards mitigating the new mother’s loneliness. Governmental and non-governmental social resources can help new mothers with their loneliness, especially those who do not have partners or close family members, neighborhood friends, or work colleagues to fall back on, but that will require the mothers to be more familiar with their local government operations and to perceive them as being reliable and caring.

A mother’s sense of loneliness was previously reported to be significantly associated with being financially worse-off, having a smaller family social network, having fewer friends, and having a smaller online social networking system (SNS) [19]. This corresponds well with our results. In our assessment of the mother’s SNS, we felt that messaging through her SNS could be a useful tool for preventing the mother’s psychological and social isolation, as a means for improving her sense of loneliness. With modern technologies, it might be easier now for mothers raising young children to have broader communications with their friends and colleagues through their SNS. For example, her SNS allows new mothers to communicate with their distant friends, and possibly more often with neighborhood friends than chance encounters would allow. However, electronic communications can never fully replace face-to-face interactions, where body language, touch, and tone have vital roles in communication. With that limitation acknowledged, going forward, we (medical and governmental professionals) need to develop novel and strong emotional and educational support capabilities for new mothers using popular SNS.

Our study has at least one limitation. Our results were correlative; we have not investigated fully whether the pandemic directly induced the new mother’s child-rearing anxiety, or her economic anxiety, or whether it was the cause of why she felt she did not have anyone whom she felt she could consult with when she had trouble or any of the other associations we found. It has often been said, “Correlation does not prove causation.” The factors associated/correlated with the mother’s increased sense of loneliness during the first year of the pandemic should be reevaluated as the COVID-19 epidemic plays out.

Conclusions

As we theorized initially, Japanese mothers with newborns felt lonely more often during the first year of the pandemic than before it. The mother’s work and economic status, her access to help immediately after childbirth, her stress over child-rearing, and her perceptions of her partner, family, friends, and colleagues consoling and supporting her, and giving her advice raising her children, were all contributors to her enhanced sense of loneliness during the beginning of the COVID pandemic. These women were also more likely to refrain from consulting their pediatric clinic due to the pandemic, which increased their feelings of isolation.

With the pandemic still ongoing, and an eye towards preventing harm to our most precious children, we should offer stronger professional psychological support to new mothers. We should also promote stronger family and friend involvement in her child-rearing efforts. Lastly, we must avoid causing any further increases in her sense of social isolation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. G.S. Buzard for his constructive critique and editing of our manuscript.

Financial Disclosure

This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grants (grant numbers JP 21H04856); the Japan Science and Technology Agency (grant number JPMJSC21U6); Intramural fund of the National Institute for Environmental Studies; Innovative Research Program on Suicide Countermeasures (grant number: R3-2-2); and Ready for COVID-19 Relief Fund (grant number: 5th period 2nd term 001). The findings and conclusions of this article are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the research funders.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Author Contributions

AM: manuscript writing, study design, interpretation of result; YU: study design, interpretation of result; AY, Toshihiro Kimura, EK, KH, SN, and Tadashi Kimura: questionnaire preparation. TT, YH and SO: supervision.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

COVID: coronavirus disease; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Survey; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; SNS: social networking system

| References | ▴Top |

- Chung EK, McCollum KF, Elo IT, Lee HJ, Culhane JF. Maternal depressive symptoms and infant health practices among low-income women. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):e523-529.

doi pubmed - Peplau LA, Miceli M, Morasch B. Loneliness and self-evaluation. Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1982. p. 1-151.

- Hubner T, Wolfgang T, Theis AC, Steber M, Wiedenmann L, Wockel A, Diessner J, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress and other psychological factors in pregnant women giving birth during the first wave of the pandemic. Reprod Health. 2022;19(1):189.

doi pubmed - Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa19/dl/14.pdf. Accessed on Sep 6, 2022.

- Declining birthrate white paper 2006. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/shoushi/shoushika/whitepaper/measures/w-2006/18webhonpen/index.html. Accessed on Sep 6, 2022.

- Rakuten Insight, Inc Tokyo, Japan. Available online: https://in.m.aipsurveys.com. Accessed on Sep 6, 2022.

- Ahmad M, Vismara L. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on women's mental health during pregnancy: a rapid evidence review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):7112.

doi pubmed - Fernandes DV, Canavarro MC, Moreira H. Postpartum during COVID-19 pandemic: Portuguese mothers' mental health, mindful parenting, and mother-infant bonding. J Clin Psychol. 2021;77(9):1997-2010.

doi pubmed - Farrell T, Reagu S, Mohan S, Elmidany R, Qaddoura F, Ahmed EE, Corbett G, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the perinatal mental health of women. J Perinat Med. 2020;48(9):971-976.

doi pubmed - Kahyaoglu Sut H, Kucukkaya B. Anxiety, depression, and related factors in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey: A web-based cross-sectional study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(2):860-868.

doi pubmed - Effati-Daryani F, Zarei S, Mohammadi A, Hemmati E, Ghasemi Yngyknd S, Mirghafourvand M. Depression, stress, anxiety and their predictors in Iranian pregnant women during the outbreak of COVID-19. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):99.

doi pubmed - Chaves C, Marchena C, Palacios B, Salgado A, Duque A. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on perinatal mental health in Spain: Positive and negative outcomes. Women Birth. 2022;35(3):254-261.

doi pubmed - Lebel C, MacKinnon A, Bagshawe M, Tomfohr-Madsen L, Giesbrecht G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:5-13.

doi pubmed - Davenport MH, Meyer S, Meah VL, Strynadka MC, Khurana R. Moms are not OK: COVID-19 and maternal mental health. Front Glob Womens Health. 2020;1:1.

doi pubmed - Wu Y, Zhang C, Liu H, Duan C, Li C, Fan J, Li H, et al. Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(2):240.e1-e9.

doi pubmed - Sun G, Wang Q, Lin Y, Li R, Yang L, Liu X, Peng M, et al. Perinatal depression of exposed maternal women in the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:551812.

doi pubmed - Racine N, Hetherington E, McArthur BA, McDonald S, Edwards S, Tough S, Madigan S. Maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):405-415.

doi pubmed - Fujiwara T, Yamaoka Y, Kawachi I. Neighborhood social capital and infant physical abuse: a population-based study in Japan. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10:13.

doi pubmed - Mandai M, Kaso M, Takahashi Y, Nakayama T. Loneliness among mothers raising children under the age of 3 years and predictors with special reference to the use of SNS: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):131.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.