| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jcgo.org |

Case Report

Volume 6, Number 3-4, October 2017, pages 65-70

Conservative Surgical Management of Uterine Incisional Necrosis and Dehiscence After Primary Cesarean Delivery Due to Proteus mirabilis Infection: A Case Report and a Review of Literature

Dominique A. Badra, b, d, Jihad M. Al Hassanb, Mohamad K. Ramadana, c

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lebanese University, Beirut, Lebanon

bDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Zahraa University Hospital, Beirut, Lebanon

cDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Makassed General Hospital, Beirut, Lebanon

dCorresponding Author: Dominique A. Badr, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lebanese University, Beirut, Lebanon

Manuscript submitted May 31, 2017, accepted July 20, 2017

Short title: Uterine Incision Necrosis Due to P. mirabilis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo451w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

We hereby describe the conservative surgical management of a case of infected uterine incisional necrosis and dehiscence after primary cesarean delivery, and report our brief review on risk factors, physiopathology and the management of this postpartum complication. We encountered a 25-year-old woman presenting to our emergency department (ED) with severe suprapubic pain and high grade fever. She had an urgent cesarean delivery performed 10 days prior to presentation due to fetal distress. At the ED, CT scan of pelvis was ordered and showed an intraperitoneal collection anterior to the uterus at the level of the uterine cesarean scar. Exploratory laparotomy showed a uterine rupture at the previous incision site. We performed resection of necrotic edges, peritoneal lavage, approximation of uterine edges with separate interrupted sutures, placement of a suction drain in the cul-de-sac and a passive drain inside the uterine cavity through the cervix and vagina. Postpartum uterine scar rupture secondary to infection and necrosis is a rare but serious complication of cesarean delivery. Conservative management by drainage and resection of necrotic edges in addition to intravenous antibiotics may be considered as an option before resorting to hysterectomy in selected young patients. A low threshold to diagnose this complication is warranted.

Keywords: Cesarean delivery; Complication; Endomyometritis; Scar necrosis; Bladder flap hematoma

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cesarean delivery is one of the oldest procedures in the surgical field [1], with rates reaching lately up to 40% of all deliveries in the USA [2]. This route of delivery has been shown to be linked with multiple short- as well as long-term complications [2]. One of these complications is puerperal cesarean scar necrosis and dehiscence. This is rare and difficult to diagnose and the patient usually presents with a picture of endomyometritis which will prove difficult to treat. Hereby we report a case of uterine incision necrosis and rupture, occurring 10 days following primary intrapartum cesarean delivery. The case was managed conservatively with drainage and debridement with the aim of preserving fertility.

We also reviewed all available data pertaining to risk factors, physiopathology and management of this rare condition. We conducted a literature search on MEDLINE database between 1998 and 2017 to identify articles reporting similar cases. All articles published in English were included. The search terms included: “Uterine scar” OR “Uterine incision” AND “necrosis” AND “infection”. Twenty-six articles were found. The lists of references of these articles were also reviewed. In total, we retrieved 17 articles reporting 23 cases similar to the present case [3-19] and one review article about the infected uterine incisional necrosis and dehiscence written by Rivlin et al in 2004 [20].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 25-year-old G5P5A0, previously healthy woman presented to the emergency department for severe suprapubic pain associated with high grade fever and yellowish malodorous vaginal discharge of 2 days duration. She reported that she underwent an intrapartum primary cesarean delivery in a different hospital, after receiving prophylactic dose of antibiotic (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 1.2 g intravenous), 10 days prior to presentation. The procedure was performed in active labor at full term with cervical dilation of 9 cm, because of severe fetal bradycardia. Her past obstetrical history was only significant for four uneventful full-term normal vaginal deliveries. On admission, she was febrile (oral temperature: 39 °C), tachycardic (HR: 105 beats/min) and normotensive (BP: 110/60 mm Hg). The physical examination disclosed a guarded abdomen, severe suprapubic tenderness, and a foul smelling yellowish discharge from the cervix. Laboratory results showed a white blood count of 15,000 cells/mm3 with 80% neutrophils, a C-reactive protein level of 340 mg/L (normal < 5 mg/L), in addition to normal electrolytes, creatinine, and urine analysis.

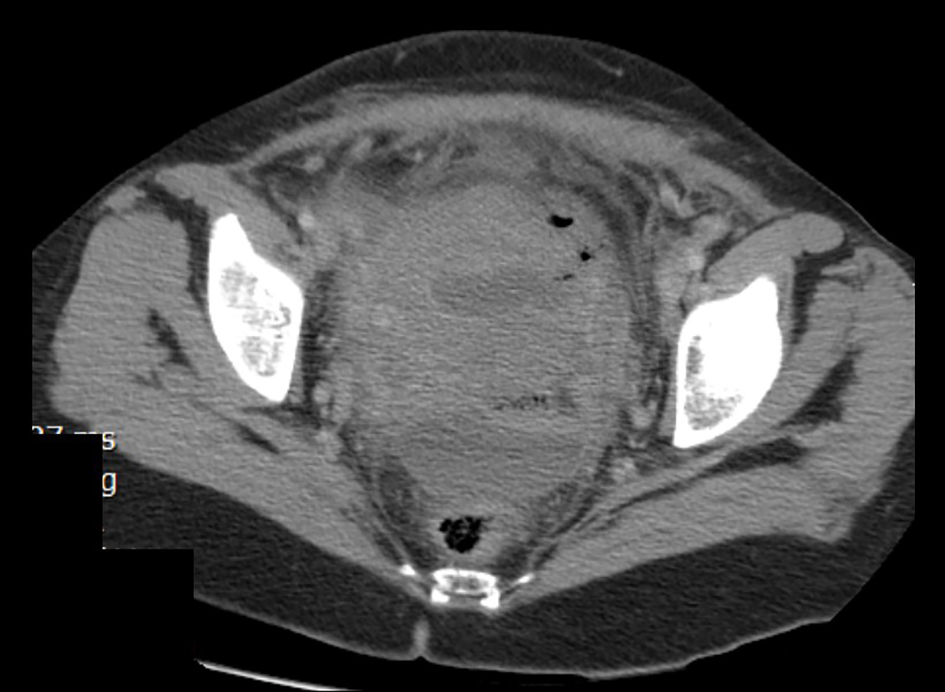

Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics were started (meropenem 1 g every 8 h) for endometritis treatment; however, the symptoms did not improve after 48 h. As a result, a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast was performed which showed a collection of 5 × 3 × 3 cm anterior to the uterine scar, and a second collection of 5 × 4 × 3 cm in the Douglas pouch (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast showing an intramyometrial gas formation, a collection of 5 × 3 × 3 cm anterior to the uterine scar and a second collection of 5 × 4 × 3 cm in the Douglas pouch. |

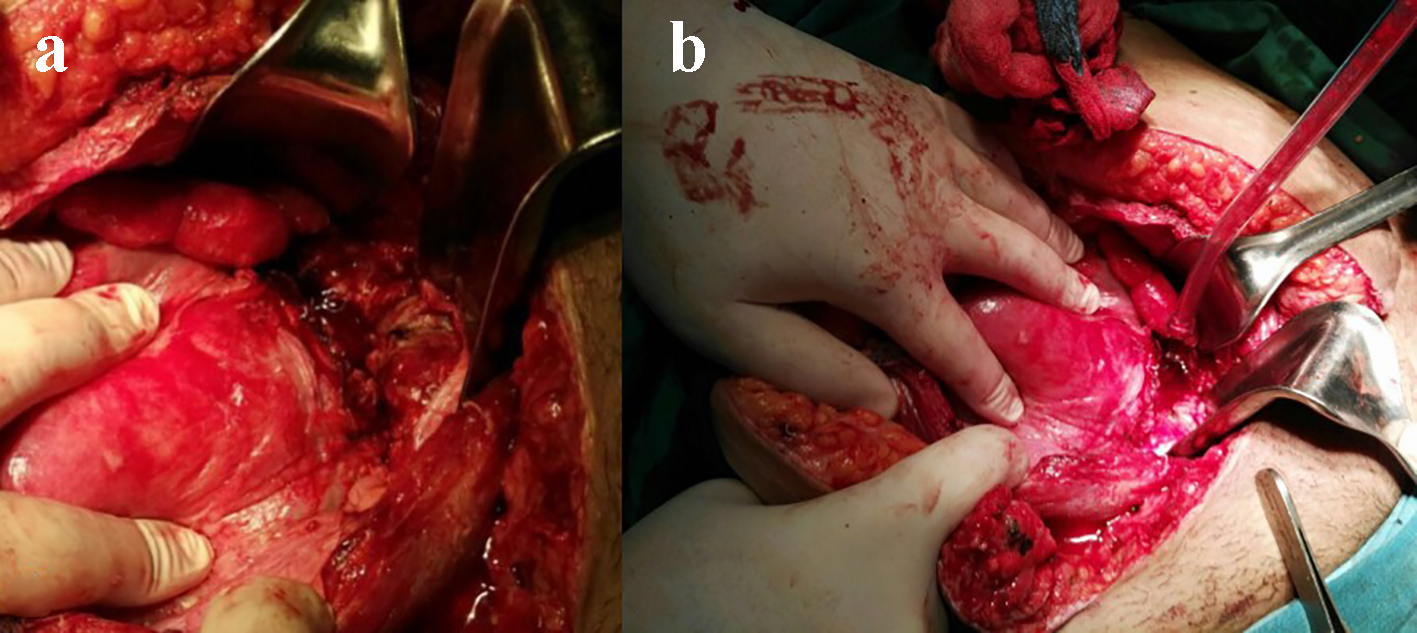

Due to the deteriorating condition of the patient and the imaging findings, an exploratory laparotomy was performed. Three hundred and fifty milliliters of pus were removed, after which a ruptured uterine scar with necrotic edges was revealed (Fig. 2a). Given the young age of the patient and her desire to preserve fertility, we decided not to perform a hysterectomy. Instead, we resected the necrotic edges (Fig. 2b), placed an intrauterine passive drain through the vagina, closed the large defect with three separate simple sutures (braided poly-filament number 2.0) because of tissue friability, and placed a suction drain in the Douglas pouch through the abdominal wall. We informed the patient about the risks of this conservative management and the possible resort to hysterectomy in case of failure.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Exploratory laparotomy. (a) Ruptured uterine scar and infected necrotic edges. (b) Debridement of the uterine scar edges. |

The pus culture grew multi-resistant Proteus mirabilis sensitive to meropenem. The patient started to improve on the second post-operative day. The intrauterine drain was removed via vaginal route on the fifth post-operative day and the intra-abdominal drain on day 6. She was discharged at day 8 post-operatively. The patient was doing well at clinical follow-up 4 months after the procedure.

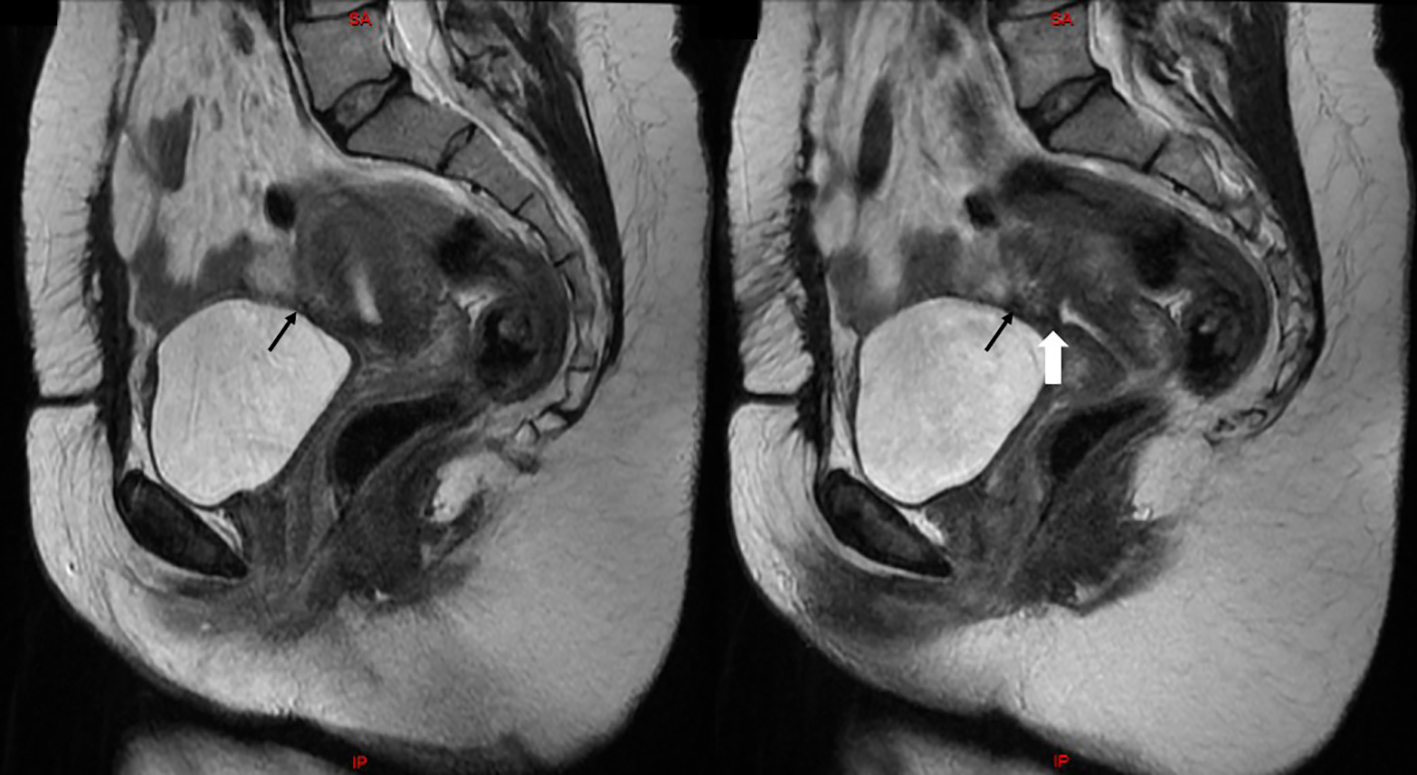

At 1-year follow-up, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis showed an intact uterine serosa, a normal endometrial thickness and only a small indentation visible at the level of the uterine scar (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Two consecutive sagittal views on T2-weighted MRI of the pelvis showing an intact uterine serosa (black arrows), a normal endometrial thickness and a small indentation at the level of the uterine scar (white arrow). |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The rate of cesarean delivery rose dramatically from 4.5% in 1970 to 32.8% of total deliveries in 2010 in the United States [2]. It is even higher in some developing countries [21]. Several factors were identified to cause this high rate, many of which are avoidable [2]. This route of delivery is associated with multiple short- as well as long-term serious complications [22]. Puerperal infection is one of the most common morbidities. It is estimated to occur three times higher in low-risk patients undergoing planned cesarean delivery compared to those undergoing planned vaginal delivery (0.6% to 0.21%, respectively) [22]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends a single-dose broad-spectrum antimicrobial prophylaxis (usually first-generation cephalosporin) for all patients within 60 min before the start of cesarean delivery [23]. Despite this practice, puerperal infection can still occur [24].

Definition and incidence

Infected uterine incisional necrosis and dehiscence is an extremely rare but a potentially lethal complication of cesarean delivery. It was defined by Rivlin et al [20] as the surgical evidence of uterine incision necrosis with or without separation of the edges of the uterine incision, subsequent to an acute infection. Due to the rarity of these cases, the exact incidence cannot be estimated.

Pathophysiology

The necrosis and the separation of uterine incision may be caused by the low perfusion to the edges due to overzealous suturing. Uterine scar weakness and dehiscence highly occur in patients with locked suturing of the myometrium compared to those with unlocked closure [25-27]. Rivlin et al [20] attribute the condition to the presence of suture material as a foreign body which constitutes a nidus for bacterial growth and subsequent cellulitis. A second proposed mechanism is that of Faro [28] who considers hematoma collection at the site of uterine incision -bladder flap hematoma - as risk factor of contamination by bacteria either directly inoculated at the time of cesarean delivery or climbing from the genito-urinary tract [29-31]. This may lead to abscess formation, myonecrosis and uterine rupture. In a study of 50 women having persistent postpartum fever, MRI showed a bladder flap hematoma in 32 patients (64%), parametrial edema in three (6%), and a pelvic hematoma in two (4%) [32]. Furthermore, the development of a severe or a sub-optimally treated endomyometritis may lead to necrosis and subsequent rupture of the uterine scar followed by formation of pelvic abscess collection. In fact, no mechanism per se can explain the exact sequence of events. Hence, it is a multifactorial condition.

Patients’ characteristics and risk factors

The mean age of patients in the 23 reported cases we reviewed was 27.7 ± 6.6 years. Most patients were primipara. Several risk factors may be involved including those predisposing to postpartum endomyometritis or postoperative hematoma formation [33-39]. In most cases, cesarean delivery was done in an emergency settings following the onset of labor and after the rupture of membranes (35% versus 22%), similar to the present case.

Clinical presentation and timing

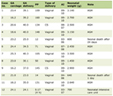

The clinical presentation of an infected uterine incisional necrosis and dehiscence may vary widely from abdominal pain and fever, to wound or vaginal discharge, heavy vaginal bleeding and sometimes to an overt peritonitis and shock if left untreated. After studying the characteristics of our patient and the 23 reviewed cases, we found that the most consistent symptoms reported were abdominal pain and/or fever not responding to intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics for more than 48 h (16 of 23 patients; 69.6%). As previously described, a pelvic abscess following cesarean delivery should be suspected in case of persistence of fever despite the use of intravenous antibiotics for more than 72 h [40, 41]. The onset of symptoms ranged from 2 to 15 days after the cesarean delivery in 16 cases but it reached 6 - 10 weeks in seven cases (Table 1) [3-19].

Click to view | Table 1. The Presentation and the Outcome of 23 Patients Having Infected Uterine Incisional Necrosis and Dehiscence Found in the English Literature |

Pathogens

Postpartum endomyometritis is usually a polymicrobial infection [42]. Several germs may be involved which enhance bacterial synergy. Aerobic and anaerobic bacteria were identified including: Streptococci, Staphylococci, Enterococcus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Proteus mirabilis, Gardnerella, Peptostreptococcus, Peptococcus, Clostridium, Bacteroids and others [42]. However, the cultures of eight cases out of 23 grew a single germ: Staphylococcus (cases 3, 9 and 14), Streptococcus (case 7), and Escherichia coli (cases 2, 5, 6 and 13). Three cases had polymicrobial infection (case 11: Corynebacterium sp and Prebotella bovi; case 12: Staphylococcus and Enterococcus; case 21: Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas and Citrobacter) as shown in Table 1. There are no previous papers reporting Proteus mirabilis as a single agent responsible of this complication.

Imaging studies

Computed tomography (CT) scan and MRI are both helpful in diagnosing pelvic masses and fluid collection [43]. CT scan findings poorly correlate with surgical findings concerning uterine incision dehiscence: an apparent discontinuity of the myometrium at the level of the incision may represent edema, and can be seen after an uncomplicated cesarean delivery [44, 45]. Another point worth mentioning is that the presence of a collection in proximity of the cesarean incision site, as seen with ultrasound or CT scan, does not mean the presence of dehiscence, and it might only reflect a hematoma at the bladder flap. In these cases, only the clinical course can determine the severity of the situation. However, compared to CT scan, MRI is more sensitive and specific in diagnosing dehiscence because it clearly delineates the uterine serosa layer [45, 46]. Nonetheless, the definitive diagnosis of infected uterine incisional necrosis and dehiscence is made during surgical exploration and it should not be based solely on imaging studies.

Treatment

The infected uterine incisional necrosis and dehiscence is a serious complication of cesarean delivery, delayed treatment of which may result in septic shock and death. Since there are no treatment guidelines based on a good level of evidence, the surgical treatment should be tailored to patients on individual basis (e.g. clinical presentation, surgical findings and patient desire to preserve fertility). In most cases, total or subtotal hysterectomy and surgical debridement with conservation of the unaffected adnexa remain the gold standard approach according to Cunningham et al [47]. Among the 23 cases reviewed, 14 underwent hysterectomy because of severe pelvic adhesions, severe peritonitis, extensive involvement of pelvic organs and heavy vaginal bleeding. In selected cases, similar to the present case, it may be possible to preserve the uterus if the patient is stable and wishes to preserve her fertility, and if the uterus and intra-abdominal organs are minimally involved by the infection. A possible surgical approach consists of abscess drainage, necrotic edges debridement, placement of an intrauterine drain through the vagina and closure of the defect.

Conclusion

In conclusion, clinicians should have a low threshold to diagnose this complication as early as possible in patients who fail to respond rapidly to broad-spectrum antibiotics. Imaging studies help clinicians to exclude several serious cesarean complications keeping in mind that the presence of a collection anterior to the uterine incision can harbor uterine scar dehiscence. Hence, the clinical presentation and the high suspicion should dictate treatment strategies. Conservative management in properly selected patients is a valid choice for cases keen to preserve their fertility instead of resorting directly to hysterectomy. However, preserving the uterus does not necessarily mean preserving fertility especially with the risk of intrauterine adhesion formation preventing conception, or cesarean scar pregnancy and uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancy.

Financial Support

No source of financial support was obtained for the report.

| References | ▴Top |

- Lurie S. The changing motives of cesarean section: from the ancient world to the twenty-first century. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;271(4):281-285.

doi pubmed - Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJ, Wilson EC, Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61(1):1-72.

- Nigam A, Gupta N, Elahi AA, Jairajpuri ZS, Batra S. Delayed Uterine Necrosis: Rare Cause of Nonhealing Wound. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(12):QD01-QD02.

doi - Dedes I, Krahenmann F, Ghisu GP, Birindelli E, Zimmermann R, Ochsenbein N. Negative pressure wound treatment for uterine incision necrosis following a cesarean section. Case Rep Perinatal Med. 2016;5(2):105-108.

doi - Bharatam KK, Sivaraja PK, Abineshwar NJ, Thiagarajan V, Thiagarajan DA, Bodduluri S, Sriraman KB, et al. The tip of the iceberg: Post caesarean wound dehiscence presenting as abdominal wound sepsis. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;9:69-71.

doi pubmed - El-Agwany AS. Postpartum uterine caesarean incision necrosis and pelvis abscess managed by hysterectomy: a complication of puerperal endomyometritis. Res J Med Sci. 2014;8;2:53-55.

- Chaudhry S, Hussain R. Postpartum infection can be a disaster. Pak J Med Dent. 2014;3(4):70-73.

- Sengupta Dhar R, Misra R. Postpartum uterine wound dehiscence leading to secondary PPH: unusual sequelae. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:154685.

- Treszezamsky AD, Feldman D, Sarabanchong VO. Concurrent postpartum uterine and abdominal wall dehiscence and Streptococcus anginosus infection. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 2):449-451.

doi pubmed - Waseem M, Cunningham-Deshong H, Gernsheimer J. Abdominal pain in a postpartum patient. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(3):261-264.

doi pubmed - Cho FN. Iatrogenic abscess at uterine incision site after cesarean section: sonographic monitoring. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36(6):381-383.

doi pubmed - Wagner MS, Bedard MJ. Postpartum uterine wound dehiscence: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28(8):713-715.

doi - Baba T, Morishita M, Nagata M, Yamakawa Y, Mizunuma M. Delayed postpartum hemorrhage due to cesarean scar dehiscence. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;272(1):82-83.

doi pubmed - Rivlin ME, Carroll CS, Morrison JC. Conservative surgery for uterine incisional necrosis complicating cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(5 Pt 2):1105-1108.

doi pubmed - Rivlin ME, Carroll CS Sr, Morrison JC. Uterine incisional necrosis complicating cesarean section. J Reprod Med. 2003;48(9):687-691.

pubmed - Blinder E, MacKenzie JD, Cranmer HH, Ledbetter S, Rybicki F. Uterine rupture with peritonitis in a nongravid uterus eight weeks after cesarean section. Emerg Radiol. 2003;10(1):57-59.

pubmed - Schulz-Lobmeyr I, Wenzl R. Complications of elective cesarean delivery necessitating postpartum hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(3):729-730.

doi pubmed - Rivlin ME, Morrison JC. Late septic necrosis and dehiscence of a cesarean incision. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 2):1044.

doi - Kindig M, Cardwell M, Lee T. Delayed postpartum uterine dehiscence. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1998;43(7):591-592.

pubmed - Rivlin ME, Carroll CS, Sr., Morrison JC. Infectious necrosis with dehiscence of the uterine repair complicating cesarean delivery: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59(12):833-837.

doi pubmed - Gibbonz L, Belizan JM, Lauer JA, Betran AP, Merialdi M, Althabe F. The global numbers and costs of additionally needed and unnecessary caesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage. WHO 2010, BP 30.

- Liu S, Liston RM, Joseph KS, Heaman M, Sauve R, Kramer MS, Maternal Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term. CMAJ. 2007;176(4):455-460.

doi pubmed - American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 120: Use of prophylactic antibiotics in labor and delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1472-1483.

pubmed doi - Tita AT, Hauth JC, Grimes A, Owen J, Stamm AM, Andrews WW. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):51-56.

doi pubmed - Yasmin S, Sadaf J, Fatima N. Impact of methods for uterine incision closure on repeat caesarean section scar of lower uterine segment. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2011;21(9):522-526.

pubmed - Ceci O, Cantatore C, Scioscia M, Nardelli C, Ravi M, Vimercati A, Bettocchi S. Ultrasonographic and hysteroscopic outcomes of uterine scar healing after cesarean section: comparison of two types of single-layer suture. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(11):1302-1307.

doi pubmed - Roberge S, Chaillet N, Boutin A, Moore L, Jastrow N, Brassard N, Gauthier RJ, et al. Single- versus double-layer closure of the hysterotomy incision during cesarean delivery and risk of uterine rupture. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115(1):5-10.

doi pubmed - Faro S. Postpartum endometritis. In: Gilstrap LC III, Faro S, eds. Infections in pregnancy, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1997: p. 65-78.

- Baker ME, Bowie JD, Killam AP. Sonography of post-cesarean-section bladder-flap hematoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144(4):757-759.

doi pubmed - Lev-Toaff AS, Baka JJ, Toaff ME, Friedman AC, Radecki PD, Caroline DF. Diagnostic imaging in puerperal febrile morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(1):50-55.

pubmed - Gemer O, Shenhav S, Segal S, Harari D, Segal O, Zohav E. Sonographically diagnosed pelvic hematomas and postcesarean febrile morbidity. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;65(1):7-9.

doi - Maldjian C, Adam R, Maldjian J, Smith R. MRI appearance of the pelvis in the post cesarean-section patient. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17(2):223-227.

doi - Acosta CD, Bhattacharya S, Tuffnell D, Kurinczuk JJ, Knight M. Maternal sepsis: a Scottish population-based case-control study. BJOG. 2012;119(4):474-483.

doi pubmed - Jazayeri A, Jazayeri MK, Sahinler M, Sincich T. Is meconium passage a risk factor for maternal infection in term pregnancies? Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(4):548-552.

doi - Kabiru W, Raynor BD. Obstetric outcomes associated with increase in BMI category during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):928-932.

doi pubmed - Leth RA, Uldbjerg N, Norgaard M, Moller JK, Thomsen RW. Obesity, diabetes, and the risk of infections diagnosed in hospital and post-discharge infections after cesarean section: a prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(5):501-509.

doi pubmed - Siriwachirachai T, Sangkomkamhang US, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M. Antibiotics for meconium-stained amniotic fluid in labour for preventing maternal and neonatal infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;12:CD007772.

doi - Tsai PS, Hsu CS, Fan YC, Huang CJ. General anaesthesia is associated with increased risk of surgical site infection after Caesarean delivery compared with neuraxial anaesthesia: a population-based study. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(5):757-761.

doi pubmed - Maharaj D. Puerperal Pyrexia: a review. Part II. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(6):400-406.

doi pubmed - Brown CE, Stettler RW, Twickler D, Cunningham FG. Puerperal septic pelvic thrombophlebitis: incidence and response to heparin therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(1):143-148.

doi - DePalma RT, Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Roark ML. Continuing investigation of women at high risk for infection following cesarean delivery. Three-dose perioperative antimicrobial therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60(1):53-59.

pubmed - Sherman D, Lurie S, Betzer M, Pinhasi Y, Arieli S, Boldur I. Uterine flora at cesarean and its relationship to postpartum endometritis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(5 Pt 1):787-791.

doi - Brown CEL, Dunn DH, Harrell R. Computed tomography for evaluation of puerperal infection. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;172:2.

- Twickler DM, Setiawan AT, Harrell RS, Brown CE. CT appearance of the pelvis after cesarean section. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156(3):523-526.

doi pubmed - Rodgers SK, Kirby CL, Smith RJ, Horrow MM. Imaging after cesarean delivery: acute and chronic complications. Radiographics. 2012;32(6):1693-1712.

doi pubmed - Maldjian C, Milestone B, Schnall M, Smith R. MR appearance of uterine dehiscence in the post-cesarean section patient. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22(5):738-741.

doi pubmed - Puerperal complications. In: Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Casey BM, Sheffield JS. Williams Obstetrics, 24th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2014: p. 675-687.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.